Once my spiritual master, Swami Rama, gave me a practice. At face value, it sounded very simple. In fact, it was so simple, straightforward, and easy that my mind hardly registered it. The core of the practice comprised remembering a mantra while focusing my mind at the center between the eyebrows. It was supposed to be done in shavasana, the corpse pose—lying on one’s back. After Swamiji finished explaining how to arrange auxiliary practices around the main practice, he said, “Make sure that, during this practice, you keep your ears plugged. Also make sure that you don’t do this practice for more than thirty minutes. If, in the middle of the practice, you fall asleep, do not start it again; wait until the next day.”

I chose 6:30 in the morning as the time for this practice. I completed it without falling asleep or without any distraction. It was very peaceful. The second day it was even more peaceful. The third day, it was so peaceful and delightful that all day long I felt like I was surfing the ocean of bliss.

The fourth day, within a matter of a minute or so, I slipped into such a quiet state of mind that I could hear the sound of my heartbeat. It became annoying. As I focused my mind with greater intensity at the center between the eyebrows, I succeeded in withdrawing the mind from hearing my heartbeat. Then the cotton ball that I was using as an earplug turned into a nuisance. The fibers of the cotton were tickling inside my ear, and it seemed as if they were moving, creating an unbearable sound. I tried my best to withdraw my mind from that sensation, but to no avail. Then I thought, “Well, earplugs are for those beginners who are distracted by external sounds. I’m an experienced meditator—I’ll take them out. Why struggle with the sound created by the fibers of these cotton balls?”

I removed the cotton balls from my ears. It felt very good. Now, without earplugs, I reached the same meditative state that I had reached the previous day, and ten minutes later, I even went a step beyond. It was an amazing experience. I was able to feel that I had a body, but it occupied just a tiny corner of my consciousness. I was awestruck with the wonder of knowing that I had a body but I was not the body.

It was so peaceful and delightful that all day long I felt like I was surfing the ocean of bliss.

In those days, I lived in one of the rooms on the second floor of the Institute’s main building. There were more than forty rooms on the wing where I lived. At the peak of my practice, I sensed someone walking in the corridor. For a few seconds, I was able to ignore it. Suddenly, my focus shattered when I heard a thundering sound coming from the corridor. It was someone’s footsteps. In the realm of my inner awareness, this sound was so explosive that it blew away my body consciousness. On one hand, I was still able to see my body lying on the floor of my room, but I could not feel it. On the other hand, I felt an excruciating pain in the subtle body that hung over the physical one. My internal faculty of perception was still intact and showed me clearly that the life force moving back and forth between the physical and subtle bodies was damaged by the sudden explosive sound. As soon as I understood that my breath was not moving in my physical body, a realization dawned: I am dead. This realization terrified me. In the field of consciousness that still filled the room and the whole wing on the second floor, I experienced pain beyond the capacity of the nervous system and brain to contain.

I looked at my wife sleeping in bed. I remembered that just a few months ago I had gotten married. I began thinking, “What will happen to her if I never come back to life? How are my elderly parents and young sisters going to withstand the shock of my death? Oh my God—I’m really dead!” The recollection of my wife, parents, and sisters, and my attachment to them, intensified my pain to the point that I began to cry loudly. Yet, in the midst of this painful experience, it was thrilling to know that there was no pain in the physical body. I thought of waking my wife, hoping she might be able to help bring me into my body. I shook her and shouted loudly to awaken her. That’s when I realized that I was doing this with my non-physical body. This realization further added to my misery. Then a thought flashed: “This whole thing happened during my practice. Had I not removed the cotton balls from my ears, this external sound would not have hit me so hard.” I also remembered that this practice had been given to me by Swamiji. At this recollection, I saw Swamiji as if he had just walked through the door.

In the vision, he entered the room, furious, and yelled at me, “I told you to keep your ears plugged!” Then his face changed. Looking at me kindly, he said, “But it doesn’t matter.” He stretched his hands toward the ceiling where I had been feeling the greatest concentration of my consciousness. As he lowered his hands toward my physical body lying on the floor, I felt myself entering it. Then he disappeared.

I regained my body consciousness. I felt that it was my body and I was in it. Still, I was not able to move it. It was numb. Then a thought flashed: “Was I dreaming? Did I fall asleep during my practice today? Did the breath of life really become disconnected? Right now, am I still dreaming?” By this time, with effort, I was able to move my toes and fingers. I worked hard. I stretched my arms and legs, and got up; however, I was still feeling weak. Holding onto the bed, I walked to my wife and woke her up. Wanting to confirm whether it had been an out-of-body experience or just a dream, I asked my wife, “Meera, was I crying?” When she said no, I concluded that this experience was neither a dream nor a hallucination.

Normally, people think that the more difficult the practice, the more advanced. From this experience, I learned that a simple, straightforward practice can open the door to the inner dimension of life, provided we do not distort it. It took generations to discover, refine, and then systematize such simple but powerful practices, and it is important that we do not become too creative while doing these practices.

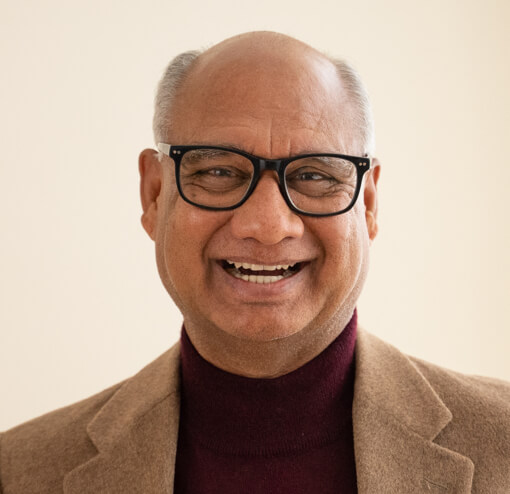

Source: Touched by Fire by Pandit Rajmani Tigunait