Modern scientists give importance to breathing exercises only from the viewpoint of oxygen intake. Their concern is with the absorption of oxygen in large enough quantities to vitalize the nervous system. But in the science of breath, this is a minor consideration. More detailed knowledge and experience is needed to study the finer forces of life than the mere intake of oxygen and output of carbon dioxide. The ancient manuals of yoga anatomy, for instance, describe a network of several thousand nadis (subtle channels) through which the currents of prana flow, energizing and sustaining all parts of the body as well as the several thousand nadis.

Principal Nadis and the Chakras

According to some manuals the number of nadis is 72,000 (others mention 350,000). Fourteen are more important than the others, but the most important among these are six: ida, pingala, sushumna, brahmani, chitrani, and vijnani. Among these six, three are the most important: pingala (surya), which flows through the right nostril; ida (chandra), which flows through the left nostril; and sushumna, which is a moment when both nostrils flow freely without any obstruction. Expansion of that moment is called sandhya. For meditation, the application of sushumna is of prime importance, for after applying sushumna, the meditator cannot be disturbed by noise or other disturbances from the external world, nor by the bubbles of thought arising from the unconscious during meditation.

These three major nadis originate at the base of the spine and travel upward. The sushumna nadi is centrally located and travels along the spinal canal. At the level of the larynx it divides into an anterior and a posterior portion, both of which terminate in the brahmarandhra (cavity of Brahma), which corresponds to the ventricular cavities in the brain. The ida and pingala nadis also travel upward along the spinal column, but they crisscross each other and the sushumna before terminating in the left and right nostrils, respectively.

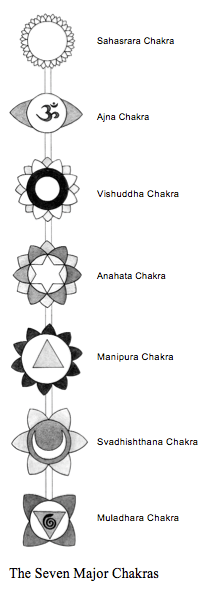

The junctions where the ida, pingala, and sushumna nadis meet along the spinal column are called chakras (wheels). Just as the spokes of a wheel radiate outward from a central hub, so do the other nadis radiate outward from the chakras to other parts of the body. There are seven principal chakras: the muladhara chakra, at the base of the spine at the level of the inferior hypogastric plexus in the physical body; the svadhishthana chakra, at the level of the superior hypogastric plexus; the manipura chakra, at the level of the solar (celiac) plexus; the anahata chakra, at the level of the cardiac plexus; the vishuddha chakra, at the level of the pharyngeal plexus; the ajna chakra, at the level of the nasociliary plexus; and the sahasrara chakra, at the top of the head. The anterior portion of the sushumna passes through the ajna chakra, and the posterior portion passes behind the skull, the two portions uniting in the brahmarandhra.

Nadis, Chakras, and the Nervous System

Yoga anatomy and physiology are clear and accurate to those who systematically study and practice the science of yoga, and they find that it reveals more about the internal functionings of the human body than any modern scientific experiment or explanation. It is true, however, that the ancient descriptions of nadis and chakras bear a remarkable resemblance to modern anatomical descriptions of nerves and plexuses, respectively. Some scientists have tried to establish a correspondence between the two systems, but the assumption behind such an attempt is that the nerves and plexuses belong to the physical body while the nadis and chakras belong to what is known in yoga science as the sukshma sharira (subtle body). In other words, they are the subtle counterparts of the nerves and plexuses, respectively. The currents of prana flowing through these nadis are the subtle counterparts of the nerve impulses.

The yogis did not dissect the physical body in order to learn about its subtle crosscurrents—dissecting the physical body to look for subtle energies would be futile. They discovered the network of nadis and chakras by mapping the flow of prana through this network, and they developed this mapping ability through introspective experimentation.

Sushumna Nadi and Kundalini Awakening

The physical body is built around the subtle framework of the nadis and is sustained by the flow of pranic energy through this network. In the average individual, the dynamic and creative aspect of prana is only an infinitesimal fraction of the total energy of prana, the major part of it remaining in a potential, or seed, state. Yoga manuals refer to this latent, stored energy as kundalini, which is symbolically represented as a sleeping serpent coiled in the muladhara chakra at the base of the spine. Further, in the average individual, prana flows through ida and pingala, but not through sushumna, this nadi ordinarily being blocked at the base of the spinal column.

The yogi is freed from the bondage of time, space, and causation.

The techniques of pranayama are aimed at devitalizing ida and pingala and at the same time opening up sushumna, thus allowing the prana to flow through this middle channel. The yogi then experiences great joy and is freed from the bondage of time, space, and causation. Then, having opened up the sushumna nadi, the yogi rouses the sleeping serpent at the muladhara chakra and guides this tremendous energy upward along sushumna, piercing the six chakras, to the seventh chakra, the sahasrara, which is represented as a thousand-petaled lotus at the crown of the head. This arousal and ascent of the latent kundalini energy and its merging in the sahasrara is synonymous with the union of shakti (cosmic potency) with shiva (cosmic consciousness). With this union the yogi achieves liberation from all miseries and bondage. He thus merges his individual soul, atman, with the cosmic soul, Brahman.

Editor’s note: In the next post in this series, Swami Rama explains how controlling the breath leads to control of the mind.

Source: Science of Breath by Swami Rama, Rudolph Ballentine, MD, and Alan Hymes, MD