In order to understand the science of pranayama it is necessary to consider the nature and function of the nervous system, for this system coordinates the functions of all the other systems in the body.

Central and Peripheral Nervous Systems

The nervous system is divided into the central nervous system (brain and spinal cord) and the peripheral nervous system, which includes 12 pairs of cranial and 31 pairs of spinal nerves that originate from the brain and spinal cord and spread throughout the body, forming a network of nerve fibers. Efferent, or motor nerve fibers, carry nerve impulses from the brain and spinal cord outward to the nerve endings, and afferent, or sensory nerve fibers, carry nerve impulses from the nerve endings inward to the brain and spinal cord.

To illustrate the functions of the afferent and efferent fibers, consider the case of stubbing your toe. The nerve endings at the toe send nerve impulses along the afferent fibers to the spinal cord and brain. The brain interprets these impulses as pain and reacts by sending motor impulses along the efferent fibers outward to the hands, enabling them to reach out and soothe the injured toe.

The autonomic nervous system is the part of the peripheral nervous system that regulates processes in our body which are not normally under our voluntary control, such as secretion by the digestive organs, the beating of the heart, and the movement of the diaphragm and other muscles that control intrathoracic pressure and therefore the flow of air into and out of the lungs.

Using Breath to Control the Autonomic Nervous System

Patanjali, the sage who codified yoga science around 200 BC, explains that the control of prana is the regulation of inhalation and exhalation. This is accomplished by eliminating the pause between inhalation and exhalation, or by expanding the pause through retention. Then, by regulating the breath, the heart and the vagus nerve are controlled. The refinement and control of the breath affect the function of the vagus nerve, which in turn affects heart rate.

The science of pranayama is thus intimately connected with the autonomic nervous system and brings its functions under conscious control through the mastery of the breath, which requires taking conscious control of the diaphragm.

Though the act of respiration is for the most part involuntary, voluntary control in this area is easily achieved, for the depth, duration, and frequency of respiration can be consciously modulated quite readily. It is for this reason that control of the breath constitutes an obvious starting point toward attainment of control over the functioning of the autonomic nervous system.

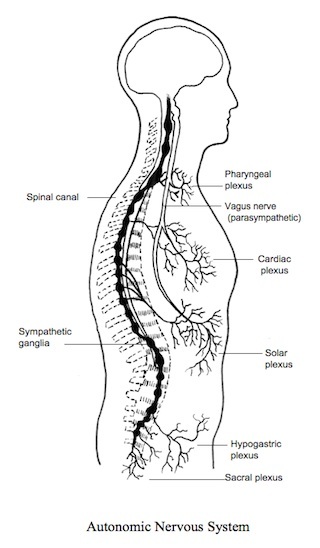

The autonomic nervous system is subdivided into the sympathetic and the parasympathetic systems. As these names indicate, these two subsystems work in seeming opposition to each other, yet the net result is harmonious regulation. The parasympathetic system, for instance, slows down the heart while the sympathetic system accelerates it, and between these two opposing actions, the heart rate is regulated. The sympathetic nervous system consists mainly of two vertical rows of ganglia, or nerve cell clusters, arranged on either side of the spinal column. Branches from these gangliated cords spread out to different glands and viscera in the thorax and abdomen, forming integrated plexuses with nerve branches of the parasympathetic system.

The main part of the parasympathetic system is the 10th cranial nerve, also called the vagus, or “wandering,” nerve. It is connected with the hindbrain and travels downward along the spinal cord through the neck, chest, and abdomen, sending out branches to form various plexuses with the sympathetic system. It ends in a plexus that is connected to the solar plexus, but is also connected with the lower plexuses through filaments.

There are only two known ways of gaining conscious control over the involuntary nervous system. One is by systematically practicing breathing exercises and preparing oneself for understanding the various vehicles and channels of prana. But first the student should learn to regulate the motion of the lungs so that heart function is regulated. Then the right vagus nerve is brought under conscious control, and the portion of the mind that coordinates with the involuntary system becomes accessible to the student. There is no such thing as an involuntary system if the student learns to regulate the motion of the lungs. For by doing so, a vast portion of that system is brought under the student’s voluntary control.

The net result is harmonious regulation.

The other way of gaining control over the autonomic nervous system is through willpower. The more the mind is dissipated, the more the will is scattered. When the mind is made one-pointed, the willpower is strengthened, and with the help of the willpower the autonomic nervous system functions the way we want it to.

Editor’s note: In the next post in this series, Swami Rama focuses on the nadis (pranic energy channels) in the subtle body, how they relate to the nervous system,and why they are important in the practice of pranayama and in attaining higher awareness.

Source: Science of Breath by Swami Rama, Rudolph Ballentine, MD, and Alan Hymes, MD