Ceaseless Activity

The story of the Gita is the story of an embattled soul. Arjuna’s despair, as we have seen, demands resolution. His thoughts are confused, and rather than fight, he has chosen to withdraw. He even considers renouncing regal life altogether and living as an ascetic.

Krishna, however, guides him toward a different worldview. Refusing to fight, he says, will lead to conflict with nature herself. The essential activities and roles of life, Krishna explains, cannot simply be set aside:

No one can remain without performing actions even for a moment. Every creature is helplessly made to perform action by the forces born of nature. (BG 3:5)

Thus the unceasing flow of action, of karma, is a fundamental principle of life. It is not possible to simply step off the wheel of karma by refusing to act, as Arjuna attempts. Action is an ongoing requirement of nature.

The story of the Gita is the story of an embattled soul.

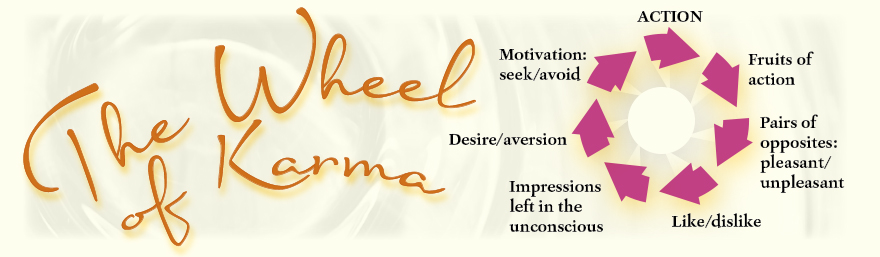

But what are these “forces born of nature” that propel action? Before exploring them in detail in the next post in this series, it would be helpful to understand how action unfolds in daily life in a cycle or wheel—the wheel of karma—that is constantly turning and returning to its origins.

The Wheel of Karma

Visually, we can anchor each element of karma on the wheel, starting with “Action” at the top. Actions, the things we do, unfailingly result in outcomes, and eventually in new action. This is true for the simplest of activities to the most complex. To take a simple example: knitting (action) leads to a scarf (result), which leads to wearing the scarf (new action).

An Instrument Designed for Action

Karma, or action, is inevitable, Krishna explains. Although the word karma is often misunderstood as the sum of good and bad results (“it’s my karma”), this word actually signifies both action and the fruits of action—what we do, as well as the results of what we do.

Just as Arjuna has his battlefield, our own lives take place on a personal field of action. There we perform daily actions using the body-mind as our instrument. Krishna describes this instrument in terms of three parts: the sense organs, the everyday conscious mind, and the faculty of discernment (also called the intellect, or buddhi). Understanding these three parts leads to an understanding of the greater purpose of life.

The senses are said to be powerful; beyond the senses is the mind; beyond the mind is the intellect. The one beyond the intellect, however, is the Self.

Thus awakening to the One who is beyond intellect, holding and supporting the self by the Self, destroy this elusive enemy in the form of selfish desire. (BG 3:42–43)

Collectively, the identity we feel using this three-part instrument is the “self” (lowercase s). The individual self is a finite presence, sustained by breath and linked to the world by the senses. In contrast, the owner of this instrument, Krishna says, dwells within it and is called the inner “Self” (capital S). Over the course of time, the individual self travels from identity to identity, ultimately seeking rest in its own essential nature—the Self.

Fruits of Action

The fruits of action are inevitably twofold: pleasant or unpleasant, successful or unsuccessful. These pairs, and countless others, characterize the relationship between our senses and the world around us. At the opening of his teaching, Krishna says:

Contact of the senses with matter is the cause of heat and cold, pain and pleasure. Being non-eternal, these pairs of opposites come and go. Learn to patiently withstand them. (BG 2:14)

In the Yoga Sutra, Patanjali refers to these pairs of opposites as dvandvas—dualistic states of mind (YS 2:48). Krishna also focuses attention on them: the verse above is the first of many times that Krishna engages with this theme.

With the approach of war, Arjuna faces several dvandvas, including the formidable pairing of victory and defeat. Arjuna’s duty, says Krishna, is to maintain equanimity in the face of either outcome and to make the encounter with this duality a source of upliftment rather than one of despair or bewilderment.

Krishna frequently uses the word “bewilderment” (moha) to describe the collective force of the dvandvas. It is the nature of life to be affected and transfixed by their continual influence:

With the rising up of desire and hatred, with the bewilderment of duality, all beings come to a state of complete bewilderment at the time of their birth. (BG 7:27)

Liking or Disliking What We See

Our experience with the dvandvas is more pervasive than we might think. Our encounter with any given action leads to a sense of liking or disliking. Generally, we favor actions that have a pleasant outcome and dislike actions that have an unpleasant one. But as we have seen, the forces that attract or repel us are the result of contact between the senses and the world.

There are attractions and aversions already facing each and every sense. One should not come under their control, for they are highwaymen waiting for him on the path. (BG 3:34)

Everyday life is a series of likes and dislikes, each a part of the web of our experience. Krishna points out the pervasive way dvandas shape our relationship with the world. We do not simply perceive, for example, that we live in a world of success and failure. We want to succeed. We are not merely comfortable or uncomfortable. We seek comfort.

We are caught up in dvandas from childhood, desiring what we perceive or imagine as pleasant, and hating that which seems unpleasant. Thus our relationship with the dvandvas (and the world) is driven by emotional reactions—reactions that distort what is true and real.

A Storehouse of Memories

With each turn of the wheel of karma, actions are recorded in the unconscious mind, often in the form of habit patterns. For instance, baked potatoes are one of my comfort foods. I can picture a brown russet potato this very moment. The experience is stored in my memory, in a portion of the mind figuratively called the karmashaya, the shed or storehouse of karma. The power of imagination makes it possible to blend the taste of the potato with the taste of sour cream and chives. Thus I make my mental pleasure complete. From an early age, enthusiasm for baked potatoes has become encoded in my memory.

Emotions supply the unconscious mind with a kind of filing system. We are linked to experience and to the need for new action by the perpetual search for happiness, pleasure, and delight. Broadly, it is the pursuit of happiness that motivates our thought patterns, and human emotion that supplies energy for our quest.

Wishes, wants, cravings, and urges lie below the surface of the conscious mind. When the objects of our desire are in short supply, and demand is magnified, emotional life is triggered to respond. The emotional intensity of a desire propels that desire to the surface of the conscious mind, where it stimulates us to act again—to seek still another serving of a baked potato, or two.

Charged with Desire

The final segment of the journey around the karmic wheel leads us to consider the question of motivation: What drives us to perform our actions? Generally, as we have seen, we pursue experience that is pleasant and avoid experience that is unpleasant. But therein lies the potential for suffering.

Actions driven by the anticipation of pleasant or unpleasant fruits, says Krishna, bind us to the pairs of opposites that accompany those fruits. Selfish attraction, or aversion, leads us to bypass the decision-making process that is meant to lie at the heart of our actions. When the wheel of karma spins without restraint, it drives us (as it drives Arjuna) to seek a mindless escape from the responsibilities life seems to impose on us.

The Gita provides a spiritual strategy for stepping away from this struggle with karma.

The Gita, in essence, provides a spiritual strategy for stepping away from this struggle with karma. This means learning to do two important things: understand the forces of nature underlying and compelling the actions that set the wheel of karma turning; and understand how four strategies, described by Krishna, lead to freedom. We will explore the forces of nature in the next post in this series and the four strategies in the following post. If you are reading along in the Gita, finish chapters 2 and 3. These introduce many of Krishna’s important themes.